Jul 22, 2005

Thumb

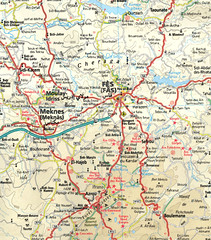

They stand along the road, a few yards west of the marche, under the trees. They're hitching, all men, some soldiers, some farmers, most out of work. The soldiers are usually on their way to El Hajeb, to visit with the prostitutes. Especially on pay day. That's the big day in El Hajib, the trucks lumber down the mountain roads and the police are always there to stop them and get money from the customers. The illegality is always unclear, always made up. In this way, the prostitutes feed everyone, except themselves. They get a pittance. Their owners, and they are often owners, collect fortunes and then build houses in the quartier de voleurs, which I told you about.

The other day I picked up a crazy looking man. He was not a soldier; he was not going to El Hajib. He was on his way to Meknes. He had a local paper. We exchanged a few words and then he went on a ramble of his own. He read all the want ads. He said he would like to go south, but when I asked why, he shook his head. He didn't know why. He carried on a conversation with himself. "I am on my way," he said in a mumble. "I'm traveling now. We're almost there. I was in airplane mechanics. At Royal Air Maroc. I hate planes, don't you? And I'll tell you this they have a real problem with parts. If they need something, perhaps for a flap, they don't get it from Boeing, they get it on a black market for those kind of parts. The parts come from Europe, or sometimes Asia. If you knew what you were flying, you would never fly. I hate altitude. Even here. What is it, a mile up? I don't like thin air. I want to get into something else. Maybe truck maintenance, but it's hard to find a job these days. Do you have any money you could spare? No, okay. That's okay. I'm just asking. You never know. But when I get to Meknes, maybe.... Where are you going after that? Oh, just there..... To fix your car. I understand. Yes, well maybe I will get to Layounne. They say it's dangerous but there's always a need for people in dangerous places. Would you like to hear the want ads again?"

Jul 21, 2005

The Ideal Moroccan

The ideal Moroccan man is tall and slender. His face is full of success and steadfastness. He has perfect teeth, perfectly white. At a lover’s distance, you might notice the scent of tobacco and perhaps frankincense from his breast pocket. He's a man you can believe. He takes great care in his appearance. His instinct is to be dapper but he confines himself to understatement. He insists that one of his daughters always prepare his travel kit, with his razor, foam and aftershave, his tooth brush and hair brush, his favorite clippers and file. And from time to time this same daughter, the one who has never deserted him, will pluck out the gray hair in his eyebrows and the stray hair between his eyes. She might also give him a facial message so that he always looks calm and untroubled, no matter if just a few hours ago there has been a disaster, if for example, he has accidentally hit someone driving home. Of course, he stopped and tried to help the person, but it was too late, and by the time the ambulance arrived, an old man on a bicycle had died.

This is one of those terrible ironies because the ideal Moroccan might be a prosecutor. And well respected. When you see his picture, you'd think he was the king, then when you see the way people greet him, the way they bow and scrape. They will kiss his hand if they can get it. He would prefer they didn't, and often hides his hand, because he is a humble man, from an enormous family further to the south. His father had 17 wives, and those were just the ones that bore children. But what makes him the ideal is that he is both traditional and modern. He knows the latest intracasies of the law, and while he doesn't use the internet himself, he makes sure the court house is well wired. At the same time, if he found out his daughters weren't virgins, he would kill them. Or, he would send them to military school, the college in Rabat for wayward girls, where one day they could become secretaries or staff in some barracks or far flung government agency. But not to worry, they obey him to the hilt. Of course, there have been problems along the way, discrepancies, things he cannot talk about. But that was before. Everyone had to survive then.

His house is immaculate. Each object has its place and he insists that everything and everyone in his house have their place, their role and arc. His wife is very beautiful. Maybe not the beauty she was once, but still distinguished in her own way. Once a week she goes to a medium who assures her that next week will bring something new and exciting and that her husband is faithful to her, no matter what she suspects. If she has not always been a kind mother, if she does not call her daughters on their birthday, it is because she has had a hard life. Her mother in turn was a monster, cold as Atlas Mountain winter, and also, let's not forget, she was married before, and beaten. The ideal Moroccan man saved her, even though she is illiterate. Because of her beauty he took her for his wife and had three children and still now, at 55, she is striking, interesting, always beautifully dressed. You would want to sit down and talk to her, through an interpreter, because she does not even speak French.

The ideal Moroccan man has a perfect sense of humor. He also knows just how to make fun of people; he can capture the essence of people in an instant. In middle age, he is proud and prosperous. He likes to hunt wild boar. Perhaps, he is a prosecutor or a government official. He is an expert when it comes to crime. He knows criminals better than they know themselves.

His children are loyal and praised by their teachers. His friends revere him. They honor him constantly. He enjoys the respect, and he is used to it. He expects respect, but in a good-natured way. “No one is kinder that this man,” you will hear people say about him. "No one is better in his profession."

"Isn't he calm?" people remark. "Have you ever seen anyone more calm that this man?" Yet, lately, he has been having horrific dreams. He can barely stand going to bed. As difficult as his days, with the problem of the prostitutes in the hotels and the corruption in the nightclubs, his nights are filled with crimes and horror. He wakes up like a man who has just been to work for 24 straight hours.

Isn't he calm and yet underneath he is on fire. Did you know he has premonitions? When his mother died he knew beforehand. Once he called one of his friends to say that he'd dreamt a pay increase was coming and sure enough it was. Another time, his wife had a car accident, not major, but he called her moments afterward wanting to know if she was okay? She is never okay anymore, but he cannot change that. And then there was the time his favorite daughter was contemplating running away to France. He dreamed that she was trying to escape the country and as soon as he woke up he told her of his dream and she was so stunned that she told him everything. Not everything but enough so that he knew how right he had been.

And if he has his secrets, his other lives, no matter. If he has learned to accept the unacceptable, it couldn’t be helped. If you understood anything about this country you would let it go. Yes, because here is the great truth: in Morocco you learn from an early age to look for people’s weaknesses. And by extension to show none of your own. How else can you survive? You must never forget, an eye for an eye. Memory as instinct. Moroccans can be very cruel to each other. No more cruel than say Americans, but it is the rifle to the handgun. Here, the injury is inflicted from a distance. You may not even know who fired the shot. It may take years before the bullet reaches you. And you may wonder, what did I do to deserve this?

Look into those dark eyes and they may say to you, I can hurt you. But why would you want to do that? You say. For fun, they might reply, laughing. And it is nothing. Just a joke. A test. Of course, you can't be sure. You have to trust in a place where there is no trust. Still, don’t pass judgment, no more than you would in an old volcano.

This is one of those terrible ironies because the ideal Moroccan might be a prosecutor. And well respected. When you see his picture, you'd think he was the king, then when you see the way people greet him, the way they bow and scrape. They will kiss his hand if they can get it. He would prefer they didn't, and often hides his hand, because he is a humble man, from an enormous family further to the south. His father had 17 wives, and those were just the ones that bore children. But what makes him the ideal is that he is both traditional and modern. He knows the latest intracasies of the law, and while he doesn't use the internet himself, he makes sure the court house is well wired. At the same time, if he found out his daughters weren't virgins, he would kill them. Or, he would send them to military school, the college in Rabat for wayward girls, where one day they could become secretaries or staff in some barracks or far flung government agency. But not to worry, they obey him to the hilt. Of course, there have been problems along the way, discrepancies, things he cannot talk about. But that was before. Everyone had to survive then.

His house is immaculate. Each object has its place and he insists that everything and everyone in his house have their place, their role and arc. His wife is very beautiful. Maybe not the beauty she was once, but still distinguished in her own way. Once a week she goes to a medium who assures her that next week will bring something new and exciting and that her husband is faithful to her, no matter what she suspects. If she has not always been a kind mother, if she does not call her daughters on their birthday, it is because she has had a hard life. Her mother in turn was a monster, cold as Atlas Mountain winter, and also, let's not forget, she was married before, and beaten. The ideal Moroccan man saved her, even though she is illiterate. Because of her beauty he took her for his wife and had three children and still now, at 55, she is striking, interesting, always beautifully dressed. You would want to sit down and talk to her, through an interpreter, because she does not even speak French.

The ideal Moroccan man has a perfect sense of humor. He also knows just how to make fun of people; he can capture the essence of people in an instant. In middle age, he is proud and prosperous. He likes to hunt wild boar. Perhaps, he is a prosecutor or a government official. He is an expert when it comes to crime. He knows criminals better than they know themselves.

His children are loyal and praised by their teachers. His friends revere him. They honor him constantly. He enjoys the respect, and he is used to it. He expects respect, but in a good-natured way. “No one is kinder that this man,” you will hear people say about him. "No one is better in his profession."

"Isn't he calm?" people remark. "Have you ever seen anyone more calm that this man?" Yet, lately, he has been having horrific dreams. He can barely stand going to bed. As difficult as his days, with the problem of the prostitutes in the hotels and the corruption in the nightclubs, his nights are filled with crimes and horror. He wakes up like a man who has just been to work for 24 straight hours.

Isn't he calm and yet underneath he is on fire. Did you know he has premonitions? When his mother died he knew beforehand. Once he called one of his friends to say that he'd dreamt a pay increase was coming and sure enough it was. Another time, his wife had a car accident, not major, but he called her moments afterward wanting to know if she was okay? She is never okay anymore, but he cannot change that. And then there was the time his favorite daughter was contemplating running away to France. He dreamed that she was trying to escape the country and as soon as he woke up he told her of his dream and she was so stunned that she told him everything. Not everything but enough so that he knew how right he had been.

And if he has his secrets, his other lives, no matter. If he has learned to accept the unacceptable, it couldn’t be helped. If you understood anything about this country you would let it go. Yes, because here is the great truth: in Morocco you learn from an early age to look for people’s weaknesses. And by extension to show none of your own. How else can you survive? You must never forget, an eye for an eye. Memory as instinct. Moroccans can be very cruel to each other. No more cruel than say Americans, but it is the rifle to the handgun. Here, the injury is inflicted from a distance. You may not even know who fired the shot. It may take years before the bullet reaches you. And you may wonder, what did I do to deserve this?

Look into those dark eyes and they may say to you, I can hurt you. But why would you want to do that? You say. For fun, they might reply, laughing. And it is nothing. Just a joke. A test. Of course, you can't be sure. You have to trust in a place where there is no trust. Still, don’t pass judgment, no more than you would in an old volcano.

Jul 20, 2005

Shall I or not?

Would you rather hear the story of the girl who grew up in Beni Mellal, and at 4 continually dug up the earth around her house looking for the dead and, not finding any, concluded that the dead disappeared, but then only to wake up one morning next to her dead grandmother?

Or about how Mohammed V took money under the carpet. Literally. This, when the royal family was destitute between the wars...

Or about how one of the professors was detained for several hours by police last Thursday after customs officials in Meknes found in a box sent from France an old cartoon, from the late 1980s, depicting Hassan II in an unflattering way?

Or about the woman from Indiana and her sexual appetite for 10 men from Sicily, one right after another, one evening 30 years ago? Or about her record collection of songs with titles like "incurrably romantic," "Romantically Helpless", and "Cold, cold heart."

Or about how children are taught to fear sex from an early age and more than that, how little girls are taught to believe, not by design of course, that you will never be happy with the man you marry.

Or about how when we walk in the forest, the dog and I, she becomes like a child when the barbary apes appear.... I tell her that could be you.

Or about how the other Friday I caught her outside the faculty club eating cous cous out of a torn plastic bag. 'What do you expect," she said, "It's a holy day." I killed her on the spot.

Or about how yesterday afternoon, on the road out of Meknes, the wind picked up and blew crazy and the sky to the east turned storm color, the color of my father's eyes just before he died. That color and yellow sand blowing in great torrents.

Or about the Hopper moment, with the psychologist sitting at her table with a drink, alone in the afternoon, with the windows wide open so anybody could see her, say hello, start something up, because she's got the lonlies, bad.

Or about how the university has issued, at the last moment, so it's too late to find another job, 11-month contracts for the coming year, to save a month?

Or about how my mother believed I was trying to poison her, to keep her here, out of love, courtly love she told someone, but of course obsessive love... how she thought I was going to kill the dog first, then her?

Or about how the Royal family, according to rumor, is in the drug trade, takes money from wealthy farmers in the Rif and launders it abroad? It's no lie, the blanchissment. The new boulangerie in Azrou is, I'm told on good authority, drug money.

Or about what the dog says as it's running by the car at 20 miles and hour?

Or about how woman no. 3 was freed by the notion, given her by a ghost of my motherm, that you must stay with your nature, that your inclinations, no matter how bizzare, no matter how fickle or silly, will save you? I had to laugh at that. It was a splendid justification of self-deception. The best I ever heard.

Or about how the police in Ceuta terrify the old women crossing the border, Spanish and Moroccan police alike, searching these women loaded down with contraband, which is good for both sides - the Spanish get more tax money; the Moroccans get 'product' to keep the blackmarket alive. Because a lot of other markets are dead. But what is a policeman to do? If he can't search someone, arrest someone, intimidate and examine, what good is he? Will his wife even believe he goes to his job every day? If he doesn't have stories of policing what can he tell his son?

Or about the paths we take through the forest every morning. Every day we try to get more lost, but the more we try the more we end up where we started. We're going blindfolded tomorrow.

Jul 16, 2005

Good afternoon, 'mam. I'm Sgt. Friday, this is my partner, Frank Smith, we'd like to ask you a few questions

Woman comes to the door. After 9 p.m. It's what's her name. She's got that look. And she gets right into it. It's the dog again. But wait a minute, what's your name? I ask. She won't answer; she just goes right on. I ask again, to nothing and so I keep asking and she keeps going. Finally, I say, I can't have a conversation with someone who won't tell me their name. She finally tells me. I can't remember it as soon as I hear it. Three names. Zs in the middle. She's the head of Housing. She's representing the community. She's got a problem with Lucy.

I said, did you get my letter? "Four pages," she says. "I read every one." "That's good," I say. "Well, what did you think?" She doesn't want to have a conversation. She wants to tell me that enough is enough. And here, it's Saturday, I've just gotten back from taking Lucy on a long walk and having tea with Gh who's told me wicked stories about monarchial mischief and the drug trade, and because it's after 9 p.m. I let the damn dog jump in and out of the window while I make dinner. There's no one outside. Yes, but then it turns out while my back was turned Lucy jumped in Cheri's window — Cheri is the resident psychologist and counselor, and boy has she got a list — Lucy jumped in her apartment and ate a bowel of spaghetti that had been left on the floor.

"You see what I mean?" said Z. I said, Look Cheri's cat jumped in our apartment and scared us half to death, Lucy particularly. And it was true. All of a sudden there's this large grey piece of dust floating by my desk, Lucy sees it and jumps straight, just like she was a cat, herself.

"What country are you from?" I asked. The next day I found out my bio-rhythms were all on the bottom line, and the prognosis is for things to get worse. She didn't answer; I kept asking. Finally, I said, "you from the Soviet Union." I thought she was. No, she said, I'm from Morocco. I got the wrong red flag, I said. I was seeing red. Do you have any family in the Red Army?

She doesn't want to talk to me, she wants to tell me about the poop. I said, 'let's talk poop.' It's not funny, she said. I said, did you not see me picking up poop the other night? Yes, you did. Admit, you saw me picking up Lucy poop the other night. She had to admit it.

Yes, she said, you did, but people have seen poop around.

Well, let's compare poops, I said. Let's line 'em all up and see who's whos. 'Cause you never know, it could be from that other dog.... And there is another dog. Little, but Lucy and that dog go to the same bar down next to the old fish market street. I seen 'em.

"I know that other dog," said Z. "But you're missing the point."

I'm telling you this quick but this was 45 minutes. Meanwhile, her son is throwing rocks at the window. I should go get him, she says, but the truth is she likes this argument. She's pregnant, frustrated and she wants to stand head to head and go at it. Every chance to leave, she stays. After a while, I'm thinking, because I've insulted her in every way I can think of, are you coming on to me...

I get her back to poops. No one has seen Lucy do it but it's the idea. And here's the worst of it, people are afraid. There are 20 people afraid. Last time she said there were 4. I said what's the inflation here. People are afraid to tell you, she said. I said, this country is still les annees noires. Is fear all you can do? Are there any other tricks you can do? Anything at all. Jump rope. Make a dime disappear. No, she said, people are really afraid. I said, are you afraid?

No.

Okay, is your son afraid? No, he loves Lucy, and he's no bigger than Lucy.

So, if you don't have fear, why don't you convey that to your commrades and maybe we can all get together, talk poop, talk fear, talk dog. And by the way when are we going to have internet service.

That set her off.

And you know my son has been a target here. Let's talk about. She goes gooey. I know, she said, and I know who did it.

Great, I say, let's worry about that and poop and blather.

No, she won't go that far. You have to keep the dog on the leash at all times. What does that mean? I ask. Because we get up every day at 6:15 a.m. and first thing I let her out, not for a poop, which I've kind of trained her to hold 'til she gets out of the residence, but just to pee and see. Then I have my sneaks on and we're off. But you're saying every moment and she goes off on how that's the law in communities around the world.

Have you ever lived in the U.S?

She won't answer. I press. She finally says she has a brother that once lived in Utah. I've looked into the laws all over America. You did? How, I ask. On the internet, she says. But there's no internet service, I say. She nods. Yes, that's true we don't have that.

I say, listen those laws were created after severe problems. Too many. We just have one hear.

One is too much, she says.

I say you got that right.

We're still standing out there and her child must be half way to Fez by now, if he's a walker.

What do you want me to do? I ask finally.

I never want to see or hear about that dog bieng off leash.

I said you're nuts. It's impossible. She'll get out. She's steal away. Why don't we sit down and address the fear issue.

I'm not afriad she said, looking at me with these wild eyes.

I said, did you get my letter? "Four pages," she says. "I read every one." "That's good," I say. "Well, what did you think?" She doesn't want to have a conversation. She wants to tell me that enough is enough. And here, it's Saturday, I've just gotten back from taking Lucy on a long walk and having tea with Gh who's told me wicked stories about monarchial mischief and the drug trade, and because it's after 9 p.m. I let the damn dog jump in and out of the window while I make dinner. There's no one outside. Yes, but then it turns out while my back was turned Lucy jumped in Cheri's window — Cheri is the resident psychologist and counselor, and boy has she got a list — Lucy jumped in her apartment and ate a bowel of spaghetti that had been left on the floor.

"You see what I mean?" said Z. I said, Look Cheri's cat jumped in our apartment and scared us half to death, Lucy particularly. And it was true. All of a sudden there's this large grey piece of dust floating by my desk, Lucy sees it and jumps straight, just like she was a cat, herself.

"What country are you from?" I asked. The next day I found out my bio-rhythms were all on the bottom line, and the prognosis is for things to get worse. She didn't answer; I kept asking. Finally, I said, "you from the Soviet Union." I thought she was. No, she said, I'm from Morocco. I got the wrong red flag, I said. I was seeing red. Do you have any family in the Red Army?

She doesn't want to talk to me, she wants to tell me about the poop. I said, 'let's talk poop.' It's not funny, she said. I said, did you not see me picking up poop the other night? Yes, you did. Admit, you saw me picking up Lucy poop the other night. She had to admit it.

Yes, she said, you did, but people have seen poop around.

Well, let's compare poops, I said. Let's line 'em all up and see who's whos. 'Cause you never know, it could be from that other dog.... And there is another dog. Little, but Lucy and that dog go to the same bar down next to the old fish market street. I seen 'em.

"I know that other dog," said Z. "But you're missing the point."

I'm telling you this quick but this was 45 minutes. Meanwhile, her son is throwing rocks at the window. I should go get him, she says, but the truth is she likes this argument. She's pregnant, frustrated and she wants to stand head to head and go at it. Every chance to leave, she stays. After a while, I'm thinking, because I've insulted her in every way I can think of, are you coming on to me...

I get her back to poops. No one has seen Lucy do it but it's the idea. And here's the worst of it, people are afraid. There are 20 people afraid. Last time she said there were 4. I said what's the inflation here. People are afraid to tell you, she said. I said, this country is still les annees noires. Is fear all you can do? Are there any other tricks you can do? Anything at all. Jump rope. Make a dime disappear. No, she said, people are really afraid. I said, are you afraid?

No.

Okay, is your son afraid? No, he loves Lucy, and he's no bigger than Lucy.

So, if you don't have fear, why don't you convey that to your commrades and maybe we can all get together, talk poop, talk fear, talk dog. And by the way when are we going to have internet service.

That set her off.

And you know my son has been a target here. Let's talk about. She goes gooey. I know, she said, and I know who did it.

Great, I say, let's worry about that and poop and blather.

No, she won't go that far. You have to keep the dog on the leash at all times. What does that mean? I ask. Because we get up every day at 6:15 a.m. and first thing I let her out, not for a poop, which I've kind of trained her to hold 'til she gets out of the residence, but just to pee and see. Then I have my sneaks on and we're off. But you're saying every moment and she goes off on how that's the law in communities around the world.

Have you ever lived in the U.S?

She won't answer. I press. She finally says she has a brother that once lived in Utah. I've looked into the laws all over America. You did? How, I ask. On the internet, she says. But there's no internet service, I say. She nods. Yes, that's true we don't have that.

I say, listen those laws were created after severe problems. Too many. We just have one hear.

One is too much, she says.

I say you got that right.

We're still standing out there and her child must be half way to Fez by now, if he's a walker.

What do you want me to do? I ask finally.

I never want to see or hear about that dog bieng off leash.

I said you're nuts. It's impossible. She'll get out. She's steal away. Why don't we sit down and address the fear issue.

I'm not afriad she said, looking at me with these wild eyes.

Jul 15, 2005

Quentin... Thanks for the kind words. But I'm afraid I'll always be seen as the villain. Forever, Lucy

I can't tell for a moment what that sound is. Is it a fly or the call of the muezzin? The faintest, most plaintive plea. Wings or voice, I can't tell. I'm standing on a mound scanning for the dog. For the fifth day in a row we have become separated. She does this to spite me, even after all the efforts I've made to please her. I will kill her as soon as I find her. I will take her head to Meknes put it on the battlements of Moulay Ismail's castle, to go along with the ghosts of 10,000 other heads.

How can this happen? I walk 30 yards, turn around and she's gone. I'm thinking maybe I have to keep her on a barbed wire leash, drag her after the car like marrieds cans. I cannot turn my back; this is the new truth. Not for a moment. So what, you think. But this problem is growing. Every day there's something. A break out, a complaint. The Islamic women the other night, standing under the court lights, and this one, I think she's the one that's leading the effort to get rid of the dog but I couldn't see very well, and just at the moment she looks at me, the dog jacknifes and shits. And she's looking up like anyone would sitting on the can, particularly being viewed. This is a long one and so here's the dog trying to get it out and the woman is beside herself trying to get the sight of the dog out — of her mind where it will be forever hanging. She's appalled that the dog is so closeby and doing this. She quickly looks and me and points behind her, as though to say, 'that's where it's buried.'

I pretend like I'm on my cell phone. I turn away.

And every day there's another distrubance . On Wednesday, Soueda finished doing the laundary and mopping the floors but left open the kitchen window, which is baracaded by plants. Just open 10 inches. The dog drips through. All the world is permeable to her.

And now at 6:45 a.m., toward the end of the walk, she does this. It's the third time this morning. The territory is no longer frightening. She's discovered discarded food and other delicacies in the refuse lying here and there. But how does she disappear so fast? You walk a few yards, look over shoud shoulder. Poof.

We're on the road above the cemetary. I see the old toothless woman, I'd seen a few minutes earlier. The dog had frightened her. She goes through entrance to the cemetary. I walk behind her and up a mound. The dog's not below, toward the town. She didn't get ahead of me. I don't think she's back a long the road we're on. Just 100 yards in that direction she'd gone off but the workmen on the roof saw her on a parallel road. And then something spooked her. A dog or perhaps a man with a stone. The workmen pointed and I turned around just in time to see her in that whippet stride, a black blur, among rocks and ramparts. I ran ahead. She rounded a corner and we collided. I said, listen, I've had it. Now just stay with me until we get home. I am in no mood. It's too early; I'm sick as a dog, you'll forgive the expression.

We walk on and 30 yards later she's gone again. I'm in a Rumi reverie and she disappears, and no poetry, no success, nothing is compensation. I want to kill her. This business of losing dogs on walks is old wood, an old letter from childhood.

So I scout from the mound and there's nothing. I don't want to go back and face the guards again. How is it that every day now this man loses his dog? they want to know. They look at me with that benevolent smile. They shake their heads. And, of course, this is something to jot down. Someone at the university will know about this by the end of the day. There'll be a slip of paper, a minute notation, lost among stack of other notations.

I double back. I walk up one street, down another. I'm trying to think this through. I end up on a street parallel to the one I'd been on. Suddenly, I notice a black shape on that other street. Running in the direction we were going. I yell. The shape stops. It's her. Not a positive ID but I'm sure it is. The shape is running again. I call again. The shape stops. I start running toward it. About a quarter mile away. The shape takes off. My first thought is that to kill her I've got to cut her off. I run hard toward the residence, across an abandonned plot, over the yellow flowers and the tiny blue flowers, I can't remember names, I get on the straight road to the residence. I'm running, but not well, I don't have juice. I'm out. I walk but I'm close enough now that I can see all the approaches to the residence. I don't see her. I slow down.

I arrive at the residence. I've gotten there first. The guards are seated in their plastic chairs, legs crossed like women in an impressionist painting. Two guards and a soldier. They look at me, say nothing. The one guard and I don't do well. He has his white holster, which is always unlatched. He hates the dog. He hates me. He looks like a man in a spaghetti western. Eli Wallach, squinting.

I often waved to the guards, because it seemed appropriate, but as I've come to appreciate their real role here, which is not about security - they're off from 4 a.m. to 6 a.m. - it's intelligence gathering, I've become less affable. I resent their duplicity. I resent their resentment. And particularly this one. When we duel, like the other day, when we passed each other, along the walk that runs along the back of the residence, I look at him directly and unlike before, when I would offer salam alecum, I wait for him to go first. I know he doesn't like that.

I feel the weight of the university lately. Not to mention the imbroglio over the electricity. In April they insisted we were all paid up. Two weeks ago they say, we owe another $100 for December. They shake their heads. "A miscalculation." And now $60 for June. How can it be? There's no air conditioning. It's light until 8:30 p.m. I don't run anything. It's 100 degrees on a lot of days. Nothing moves. I don't cook anything. I don't light anything. Lucy and I live in dim light. Just enough to read. How can we pay the same rate as in February when we were burning everything. If there was a lighbulb we turned it on. The appearance of heat was important.... So now I'm asking them for kilowatts and rates for each month, not just the amounts due. In the interests of transparency. You want an American-styled university, then be it. But they won't show me kilowatts or rates. They're stalling.

My friend, S., smiles when I tell him this. "Of course," he says. "They're cheating you because they need more money to pay for the new heating system." He encourages me to battle them. But it's dangerous, there is a danger here.

So I come in the gate. No dog. No word from the guards.

I get to the building. She's sitting next to the door, like 'Oh King, where hast thou been?' She's panting. She's been moving.

I kill her.

Later, inside, I notice she smells bad. Not like she rolled in something, like she became something. In afterlife, I chase her into the bathroom. I give her a bath. She's out of emotion. I tell her, You're not going back to another life. You're going back down to a be bug. Meanwhile, she's looking confused, the water, the soap, the man who just killed her is now giving her a bath... Can you beat that, Pa? These Americans are weird, aren't they though?

Jul 13, 2005

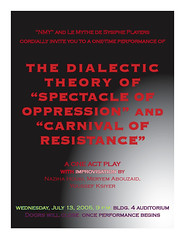

Invitation to a play

Three actors, all undergraduates. Two girls, a boy. And one other actress drawn in at the last moment to do a little routine before the play started. As for the play itself, we put together a series of emotional plots, then improvised dialogue, practiced the improvisation and went live last night. Some of the plots were chosen by the actors, out of personal experience. Some we made up. Six scenes: Woman trying to talk to her father about an affair she was having with a married man; two women, one thin, one fat, exchange their bodies; a policeman interviews a veiled woman he suspects of being a terrorist; a woman who has just been raped talks with a friend; a woman confronts her mother; a young man discovers his fiance is not a virgin.

You could hear a pin drop, said a friend who watched it. Which is unusual because Moroccan audiences are notoriously edgy and not easily held. This lasted an hour. It seemed to work. What was significant was the degree to which the actors can improvise; the degree to which they don't need dialogue, merely emotional points to touch.

In the fall, we'll try for something more ambitious.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)